The first church built in Dunedin was completed in late 1873. Although, there were issues with its spire which needed to be rebuilt because it was almost 4 metres too short and had a lean. The spire was eventually finished in 1875.

And what is this church called?

First Church of Otago.

The Free Church of Scotland was formed in 1843 when approximately one third of the Presbyterians broke away from the Established Church of Scotland. This is important for the building in the photo because it was a group of 350 people who sailed to Otago in 1847, most of them selected because of their support for the Free Church and its belief that the congregations should select the ministers and not the wealthy, who were the forebears of this church in Dunedin.

The selection of the ‘right’ people who sailed on that trip was left to Reverend Thomas Burns. And it was Reverend Thomas Burns who laid the foundation stone of First Church in May 1868.

I found most of this out on my walk this morning, and it fascinated me because of this statue.

Seated almost centre stage above the town square, called the Octagon, which is an eight-sided plaza – something else Dunedin is famous for, but a nightmare to try to navigate in a car, is Robert Burns – who was well dead before Dunedin was even thought about.

And here is the coincidence and the link to First Church of Otago – Reverend Thomas Burns was the nephew of Robert Burns, the famous poet.

The early Scottish settlers here revered Robert Burns – hence the prominent statue. And around the statue were lots of plaques in the pavement recognising the contributions of other significant writers.

I then stumbled across a more modern gallery to writers and artists in a nearby alleyway.

Looking in another direction from Robert Burns, was this church.

This is an Anglican cathedral and the seat of the Bishop of Dunedin. This building was commenced in 1915, on the site of the original St Paul’s Church after a wealthy Dunedin businessman died in 1904 and left his money for its construction. On a few provisos which were obviously met 11 years later.

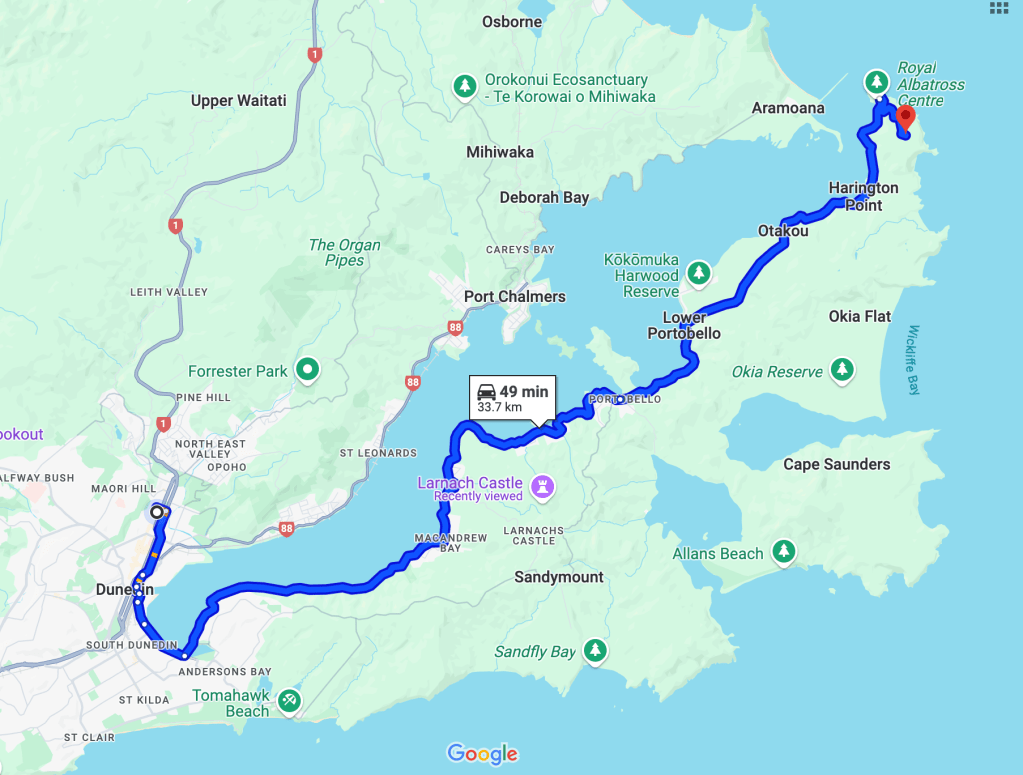

During the morning Mick and I took a leisurely drive along Portobello Road, which hugs the bay, until we reached the Albatross Centre.

Unfortunately we had not timed things well and therefore only had a short while here to enjoy the views and the abundant wildlife.

Our next stop was Larnach Castle, where we spent a few hours learning about the history of the castle and its original owners.

The view from the very top was impressive.

And in another direction…

The castle has been restored extensively, but not completely, and I preferred Olveston House to this home. The most impressive features of this house / castle were its ornately carved ceilings. This is just one of them.

The castle was designed by the architect who also designed First Church of Otago – Robert Lawson. Lawson designed it for William Larnach, who was at that time the Bank of Otago’s Chief Colonial Manager, having been sent to Dunedin in 1867.

William Larnach bought the land in 1870 after discovering it when he was out walking with his then 9-year-old son Donald.

It took more than 200 workmen three years to build the Castle shell and master European craftsmen spent a further 12 years embellishing the interior.

Materials from all over the world were used for the construction, including slate from Wales, mosaics from Belgium, marble from Italy and timber from Tasmania. To work with the materials he employed craftsmen from around the world too, including wood carvers from England, stonemasons from Scotland and plasterers from Italy and France.

The family moved into the castle in 1874. They would have lived there with all the tradesmen working around them.

William Larnach was an interesting character, who was a successful businessman and a respected New Zealand politician.

Originally born in New South Wales in 1833, William Larnach’s working career started in 1850 with the Bank of NSW. He took a break from banking for 4 months in 1851 when he joined the gold miners in the field, before returning to the bank, this time in Ararat. Perhaps he did not find much gold??

Larnach married Eliza Jane in 1859. He was 26 and she was 17. Children then came quickly – Donald (1860), Kate (1862), Douglas (1863) and Colleen (1865).

Following a family trip to London in 1866 to visit his (rich and well-connected) Uncle Donald, where he met influential banking magnates who were setting up banks in gold mining areas, he was offered the job in New Zealand (in 1867).

The following year, in 1868 a fifth child was born – a daughter called Alice.

Ten years later (in 1878), the whole family travelled to England. Here Eliza Jane gave birth to her sixth child, another daughter called Gladys. This made a 20 year gap between her first and last child. Poor Eliza is what I thought.

Most of the family returned to Dunedin and to the castle, with the older children staying to complete studies.

Eliza Jane found the isolation of the castle too much and was distressed at leaving some of her children in England. Her sister Mary came to live with her and the children (but I am unsure when in the timeline this happened) as William Larnach was away a lot with his work as a politician (he was originally elected as MP for Dunedin in 1876).

The information on display said that Eliza Jane died in 1880 of apoplexy. She was 38. In another display it said she was heartbroken.

The story then gets more complicated. Here are some key points I read…

1881 – the year after Eliza Jane died, Larnach proposed to her sister Mary. He completed pre-nuptial agreements signing over the castle, its belongings, the horses and the carriages to Mary (something to do with financial issues). Let’s just say that Donald, now 21, and his siblings were not thrilled about this.

Larnach was only legally able to propose to and marry his deceased wife’s sister thanks to the passing of legislation a few months earlier.

The Deceased Wife’s Sister Marriage Act of 1880 was a New Zealand law that made marriages between a man and his deceased wife’s sister valid. The act was controversial and divisive.

This blew me away!

I subsequently read that a similar act was passed in the UK even later, in 1907.

WIlliam and Mary married in 1882 (Gladys was now 2 years old).

Mary was not popular with the children or the staff. She liked a “tipple” and needed to spend time in her room (? sobering up). This was written on the information boards – I am not making it up. Mary died in 1887, aged 37 after being married for 5 years. Another poor woman in this tale.

Mary’s will left equal shares in the estate to the 6 children. Phew!

WIlliam, now aged 53, was not happy about that. He ordered his children to sign a document without them knowing what they were signing. Idiots! The document basically had them relinquish their rights to their inheritance.

In 1891, four years later, William married his third wife, Constance – 35 years old and from Wellington. He bought a house in Wellington where they lived next door to the Sneddons. Richard Sneddon was the 15th Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1893 until his death in 1906.

The same year he married his third wife, 1891, Larnach’s eldest daughter Kate died from Typhoid. She had been working as a volunteer nurse. Kate was said to be Larnach’s favourite daughter.

Rumours then abounded that Constance (his third wife) and William’s (second) son Douglas were having an affair. This all eventually became too much and WIlliam shot himself in a Committee Room in the New Zealand Parliament House in 1898. He was 65 years old.

Bloody hell. That’s what I thought.

But it got worse. He died without a will. That meant his wife Constance got a thrid of his estate and the children had shares in the remainder. Donald and the two older girls challenged this in court, stating they had been made to sign documents without knowing what they meant. Interestingly, Douglas sided with his step-mother.

But Donald and his sisters won the case.

In 1906, Donald sold the castle and in 1910 he too took his own life.

The castle was bought in 1967 as a derelict building and the people who bought it want it to remain as a historical home for New Zealand.

Just one of the rooms in the castle.

Interestingly, the family who owns it now have owned it for longer than the Larnach family.

In a way, it has some very sad tales to tell.

Tomorrow we head back towards wine country.